We arrived in Nova Scotia on a ferry that resembled a bus more than a sea going vessel but leave

for Newfoundland on a real ship; it even has a helipad on deck. The crossing takes six and a half

hours and as we approach the coast, we have our first glimpse of a stark landscape reminiscent of

the west coast of Scotland.

The scenery on the drive from the ferry to our first stop is spectacular; impressive mountains rise dramatically to the east, a solid vertical wall dissected by steep sided valleys. The lower lands are a wild, windswept scene of rocky outcrops, low lying vegetation and water.

We're really excited to be here and can't wait to get going. We're planning to spend our first night in Codroy Valley, take some time bird-watching and then move north. Things do not go quite according to plan. Problems with the server supporting our various websites and apps have been brewing for a couple of weeks and Sterling has been driven to distraction a number of times in his attempts to resolve them. On our first day on Newfoundland, the situation develops into a full blown crisis and all plans of travel go out the window. For the next five days, Sterling works his socks off getting a new server up and running and while this resolves the problems it leaves a trail of work in its wake. The work comes to dominate our time here; we completely change our plans and resign ourselves to travelling only the west coast, but we have already fallen under the Newfoundland spell and resolve we will return.

The first flurry of work over, we head for the settlement of Norris Point and a night in the Sugar

Hill Inn for our anniversary. The Chanterelle restaurant at the inn provides the celebratory meal

and Sterling eats the namesake fungi as part of his dinner. The chanterelles grow locally and we

see what we suspect are the mushrooms in question the following day on a short walk up Burnt Hill

but are not confident enough in our identification skills to pick and eat them.

The first flurry of work over, we head for the settlement of Norris Point and a night in the Sugar

Hill Inn for our anniversary. The Chanterelle restaurant at the inn provides the celebratory meal

and Sterling eats the namesake fungi as part of his dinner. The chanterelles grow locally and we

see what we suspect are the mushrooms in question the following day on a short walk up Burnt Hill

but are not confident enough in our identification skills to pick and eat them.

The trail climbs a short way and the views open up. It is a crystal clear day with a brisk breeze

whipping the water into white riders, the colours accentuated in the bright sunshine. Viewed through

the firs, brightly coloured buildings sit on the shore against a backdrop of bright green cultivated

grass and the yellowy green mottled pattern of the natural ground cover.

The blues and yellows of

local boats nestle at the quay, the waters in the bay a deep dark blue highlighted by the white edged

waves, the surrounding mountains stand covered in the dark colour of the evergreens, giving way to

the soft earth hues of exposed rock on the distant cliffs across the bay.

The blues and yellows of

local boats nestle at the quay, the waters in the bay a deep dark blue highlighted by the white edged

waves, the surrounding mountains stand covered in the dark colour of the evergreens, giving way to

the soft earth hues of exposed rock on the distant cliffs across the bay.

The waters of Bonne Bay reach several kilometres inland from the Gulf of St. Lawrence before splitting into two significant tidal channels known as East Arm and South Arm. Norris Point is a naturally protected harbour, on a small area of land jutting out into the waters between the two arms. Like many settlements here, it is strung out, lacking an identifiable centre, the houses intermingled with occasional small businesses.

The highlight of the west coast is Gros Morne National Park and that's where we're headed next: to Lomond campground on the East Arm of Bonne Bay, looking across the water to the steep, scree covered slopes of Killdevil Mountain. It's quite the setting and virtually empty at this time of year. We've come to get some more work done and to wait out the bad weather that is forecast but also to see something of this side of the park.

Our first venture is along Lomond River Trail where we encounter mud reminiscent of British walking paths. While it piques our interest with numerous moose tracks, we return without a sighting but with boots that need a thorough clean and trousers destined straight for the laundry basket.

In pursuit of something more rewarding we drive over to the Look Out trail that reputedly has some of

the most spectacular views in the park.

The weather is definitely against us; the mist is down

and as we climb up through the mixed woodland and out onto the boardwalks that cross the fragile

vegetation on the tops, the visibility decreases dramatically and we see nothing of the views and

very little that is further than a hundred feet away. The mist rolls up the hillside, drifting across

the rounded curves of the land, leaving droplets of moisture on hair and clothing. It is truly

atmospheric and while not ideal weather conditions it is a vivid experience of one of the moods of

the park and we're rewarded with a sighting of three moose.

The weather is definitely against us; the mist is down

and as we climb up through the mixed woodland and out onto the boardwalks that cross the fragile

vegetation on the tops, the visibility decreases dramatically and we see nothing of the views and

very little that is further than a hundred feet away. The mist rolls up the hillside, drifting across

the rounded curves of the land, leaving droplets of moisture on hair and clothing. It is truly

atmospheric and while not ideal weather conditions it is a vivid experience of one of the moods of

the park and we're rewarded with a sighting of three moose.

Our last short walk on this side of the park is at Tablelands, a windswept, bare rocky landscape that

is a section of ancient ocean floor. The ground is strewn with varying sized pieces of the orange

brown bedrock, cold streams tumble through the rocks and alpine plants, pitcher plants and tortuously

twisted evergreens survive in what at a casual first glance looks like a stark and barren place.

Our last short walk on this side of the park is at Tablelands, a windswept, bare rocky landscape that

is a section of ancient ocean floor. The ground is strewn with varying sized pieces of the orange

brown bedrock, cold streams tumble through the rocks and alpine plants, pitcher plants and tortuously

twisted evergreens survive in what at a casual first glance looks like a stark and barren place.

Green Point is another fantastic campground and we are fortunate enough to claim one of the cliff top

pitches looking over the cove to the settlement of the same name; a handful of houses just above the

high waterline. Some more work is called for but we also squeeze in a late afternoon walk on the

coastal trail.

Green Point is another fantastic campground and we are fortunate enough to claim one of the cliff top

pitches looking over the cove to the settlement of the same name; a handful of houses just above the

high waterline. Some more work is called for but we also squeeze in a late afternoon walk on the

coastal trail.

The wind is fierce and the sea quite frisky although the line of flotsam thrown high on to the land

behind the rocky beach suggests that this may be comparatively calm. Some of the land along the coast

is open grassland with ponds and lakes lying among the golden autumnal vegetation. Elsewhere, there

is a dense impenetrable forest of dwarf balsam fir and spruce known in Newfoundland as Tuckamore. It

is interwoven and twisted together, created and sculpted by the winds and salt spray. It holds

together as one entity and beneath the dense sweeping canopy are occasional gaps along its edge, a

shelter just large enough for one or two and a glimpse into the dark unreachable interior.

The highlight of our hikes in the park is of course up Gros Morne itself. I have to confess to

wimping about doing this trail. The dire warnings issued by the park include such choice descriptions

as “The view from the top is renowned as is the exhausting climb up the gully.”, “This is a strenuous

climb up a steep and rocky scree slope. Loose boulders may shift underfoot. Do not climb down this

section.” “This is not an easy hike!!”, “The long descent from the back of the mountain is

gruelling.”. Having read all this, I had started to feel it was beyond me but I'm glad to say I

got over it and up we went.

The first four kilometres of the trail gradually climb from sea level up through woodland emerging into the open overlooking a line of small ponds strung out at the base of the mountain itself. This is where the serious business starts. The trail heads out across the lower fan of the scree slope and quickly starts to climb upwards into the gully. Underfoot are boulders of every size and shape. Most of the time it's just slow going but a number of times I have to resort to the all fours mode of transport as the only way to maintain balance and make headway. The descriptions do not exaggerate; it's a hard slog, not just because of the terrain but also because of the gradient; it's a five hundred metre gain in altitude in about a kilometre and a half.

The views from the top are as promised magnificent, stretching out to the two arms of Bonne Bay. We

are more than a little pleased to have the climb behind us and to have arrived in a very different

world. The top of the mountain supports tundra at the lowest latitude in North America. Caribou spend

the winter on top, moving as the mountain becomes busier in the summer months. There's not a tree in

sight, not even of the stunted, gnarled variety. Rocks and lichens are the order of the day as we

follow the well marked trail across the top. Ahead of the first snow, Rock Ptarmigan are already

beginning to change and while much of their body plumage is a mixture of summer and winter colours,

their legs and feet are already covered in fluffy white feathers; cold weather shoes and trousers if

ever I saw them. Small flocks of Horned Lark flit about but it won't be too long before they make for

lower elevations. We sit and eat our well earned lunch whilst gazing off into the distance; statutory

sandwiches of course, double rations on this occasion.

The views from the top are as promised magnificent, stretching out to the two arms of Bonne Bay. We

are more than a little pleased to have the climb behind us and to have arrived in a very different

world. The top of the mountain supports tundra at the lowest latitude in North America. Caribou spend

the winter on top, moving as the mountain becomes busier in the summer months. There's not a tree in

sight, not even of the stunted, gnarled variety. Rocks and lichens are the order of the day as we

follow the well marked trail across the top. Ahead of the first snow, Rock Ptarmigan are already

beginning to change and while much of their body plumage is a mixture of summer and winter colours,

their legs and feet are already covered in fluffy white feathers; cold weather shoes and trousers if

ever I saw them. Small flocks of Horned Lark flit about but it won't be too long before they make for

lower elevations. We sit and eat our well earned lunch whilst gazing off into the distance; statutory

sandwiches of course, double rations on this occasion.

From the northern edge of the top, there are spectacular views of Ten Mile Pond, sitting in a deep,

near vertically sided canyon. A small lake sits in a dip on the top of the opposite side of the

canyon, a waterfall cascading over the lip. Further along an interlocking valley hangs, much work

still to do before it reaches the pond.

From the northern edge of the top, there are spectacular views of Ten Mile Pond, sitting in a deep,

near vertically sided canyon. A small lake sits in a dip on the top of the opposite side of the

canyon, a waterfall cascading over the lip. Further along an interlocking valley hangs, much work

still to do before it reaches the pond.

The descent down Ferry Gulch is no where near as bad as I'd feared and the views more than make up for the effort. We're not quite finished with scree slopes either but at least this is traversing rather than climbing them. It might not be gruelling but it's tiring and we feel every one of the sixteen kilometres when we finally get back to the camper seven and a half hours later.

The following day we decide on a different mode of transport and take the last boat trip of the year

on Western Brook Pond, a former fjord that is no longer open to the sea. Over time the coastal area

has been filled-in creating a large expanse of bog dotted with lakes of varying sizes and as we walk

the trail towards the boat jetty the distinctive profile of the former fjord is clearly visible, a

large notch bitten out of the Long Range Mountains.

Unlike a true fjord the water in Western Brook Pond is fresh, the original salt water long since gone. A number of factors combine to produce some of the purest water on the planet, so pure that it barely conducts electricity. While the surface water may reach sixteen degrees Celsius by late September, the depths remain at a steady five degrees making it a challenge for many living organisms and also slowing the process of decay. Another characteristic of the water is that it is very low in nutrients and consequently cannot support the algae which constitute the lower links of a water based food chain. While the body of water may be fascinating it is the stunning scenery which steals the limelight.

It’s a bright sunny day, the colours strong and vibrant but at this time of year the sun is low

enough in the sky to keep one side of the pond in shadow for much of the trip. The near vertical

walls are over two thousand feet high, the lower reaches covered in the yellowing colours of autumn,

the bare rock of the upper cliffs stark in contrast. As the boat makes its way along the deep blue

lake, the profiles change continuously, reflections mirrored in the water create stunning symmetrical

multi-coloured patterns and our wake produces wonderful water sculpture.

On the way back to the camper we stop at the Lobster Cove Head lighthouse where the distinctive Newfoundland accent manifests itself in the signal flags flying in the brisk breeze. The system was developed to facilitate communication between ships and the shore. Each flag represents a single letter but also double as distinct messages when posted on their own. For example; J signals "I am on fire and have dangerous cargo on board: keep well clear of me." Wise advice!

The flags flying today spell out “mudder” and the ranger delights in trying to get us to guess what

this means before she finally reveals that it’s the Newfoundland pronunciation of mother. Speech here

reminds me in some ways of accents in Ireland, and I suppose that’s not too surprising given the

number of Irish settlers and the isolation of the province. The particular ‘t’ or ‘d’ that replaces

the ‘th’ in certain Irish words is also evident in Newfoundland and the general cadence is reminiscent

of an Irish brogue. The characteristic sound of language here stands out amongst other English

speaking accents in Canada that have a greater similarity to those found in the northern states

of the US.

The French versus English issue adds another interesting dimension. When we were in Alberta some years ago, it seemed to us that English was the primary first language, with French in little evidence. This year, travelling in the eastern provinces, we found that French is much more widely spoken in the Maritime provinces than we had expected while in Newfoundland and Labrador we encountered English exclusively. In Québec the opposite is true with French the official language. Given neither of us have ever learnt à parler français, this was something of a challenge, particularly on the pronunciation front. Some years ago, when travelling in France we had a phrase book that advised using an outrageous French accent when speaking the language so we adopted this again and it seemed to work fine - just imagine either Pepe Le Pew or ‘Allo ‘Allo! The only real problem we face is at the ARRÊT signs where Sterling assures me that if we were meant to stop, the sign would say STOP.

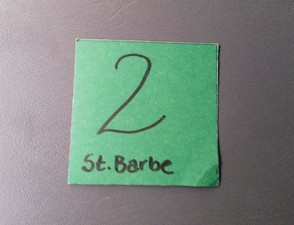

It’s time to leave this fascinating island and while our arrival on Newfoundland was uneventful, our

departure is less so. We get up before dawn aiming to catch the afternoon ferry to Labrador. The wind

is up, the sea looking wild as we drive north to St. Barbe. You can see where this is going - the

ferry is cancelled. If I try to detail the fandango that ensued, you would not believe me. I will

restrain myself by simply mentioning the truculent ticket office staff, the lack of information for

prospective passengers and the arbitrary distribution of small green squares of card adorned with

hand-written numbers. Somehow we are lucky enough to get our mitts on #2 ensuring that we are on the

eight o’clock ferry the following morning as it leaves the dockside at a quarter past nine.

It’s time to leave this fascinating island and while our arrival on Newfoundland was uneventful, our

departure is less so. We get up before dawn aiming to catch the afternoon ferry to Labrador. The wind

is up, the sea looking wild as we drive north to St. Barbe. You can see where this is going - the

ferry is cancelled. If I try to detail the fandango that ensued, you would not believe me. I will

restrain myself by simply mentioning the truculent ticket office staff, the lack of information for

prospective passengers and the arbitrary distribution of small green squares of card adorned with

hand-written numbers. Somehow we are lucky enough to get our mitts on #2 ensuring that we are on the

eight o’clock ferry the following morning as it leaves the dockside at a quarter past nine.